Empathy For a “Creep”

Why does One Hour Photo ask us to empathize with Sy (Robin Williams), and why does the film force us to do just that? That’s a question I keep asking myself. It doesn’t take long to establish the idea in our minds that Sy is a creep and may be best left alone, and yet I think it is so important that we do get to know him.

It doesn’t matter that he’s got a strange obsession with a family he develops photographs for, it’s his loneliness which in turn becomes desperation for a connection which transforms again into delusion about his place in the Yorkin family or at his job.

That may be something we can all relate to, an extreme need for a connection, just one connection and a fantasy to fill our hearts up.

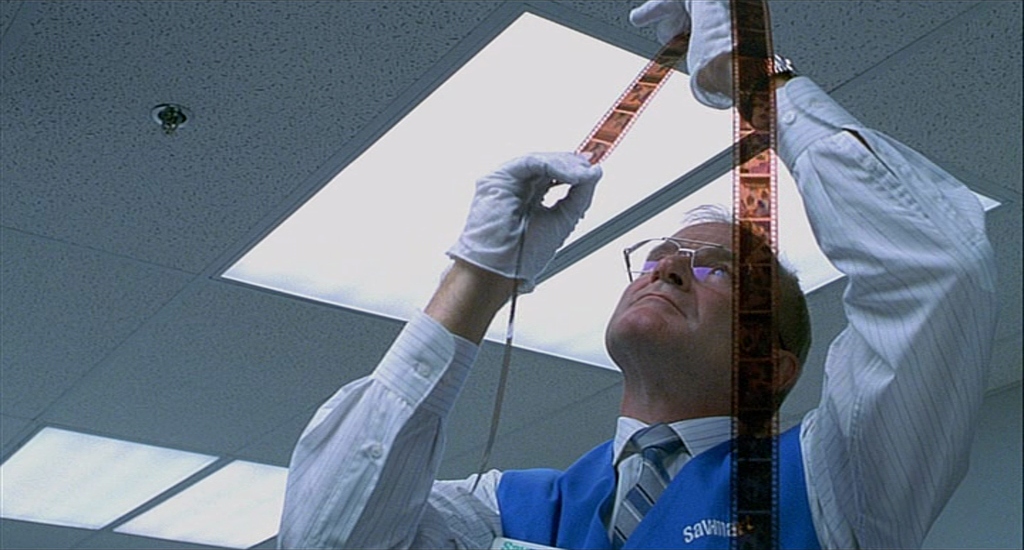

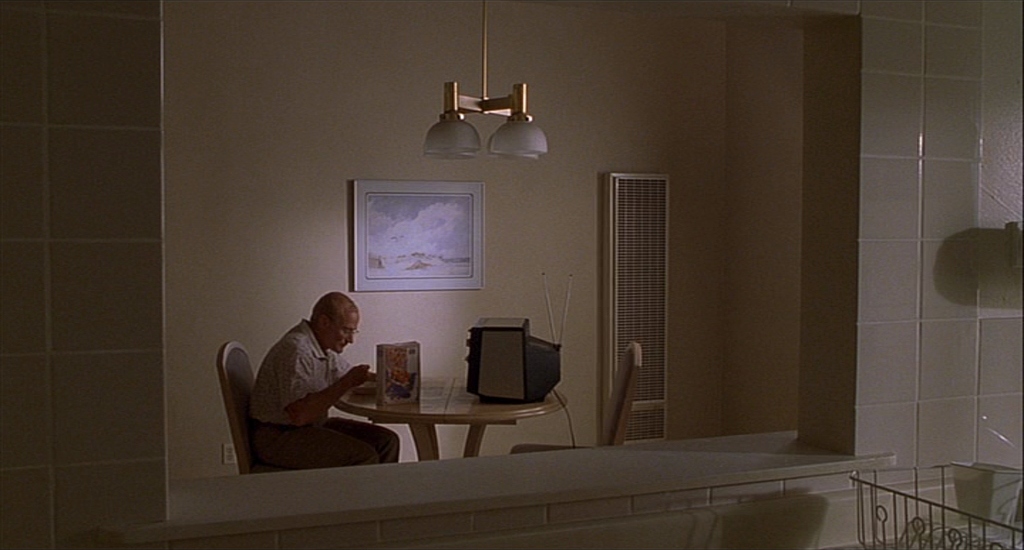

Sy is constrained, at first, by his surroundings and clever cinematography, always stuck in a frame within the frame of the film, stuck behind that desk at SavMart or seen through an indoor window.

Romanek, the writer and director, then takes it further, with Jakob Yorkin (Dylan Smith) expressing his worry for Sy to his mother Nina (Connie Nielsen) – the boy worried he is lonely. He’s right to be worried.

Nina of course brushes this off, and reassures him, even goes as far as praying with her son for Sy. We know he’s lonely, and so this scene only works to further entrench our capacity to empathize or even pity Sy.

Fantasy begins to overflow in Sy, it puts him on edge. He begins to involve himself in the Yorkin’s life, it isn’t enough anymore to be a bystander, to have stolen copies of years of their photographs meticulously plastered on his living room wall, to put forth that he sometimes thinks of himself as “Uncle Sy.”

He is mistaken to believe he means more to the Yorkins that he actually does.

Maybe it could’ve been enough, but his discovery through photographs, of Will Yorkin’s (Michael Vartan) affair with Maya (Erin Daniels), doesn’t make it so. Now he must actually involve himself beyond the occasional daydream or planned food court encounter with Nina.

We empathize with him still, even if he isn’t exactly a moral person. He regularly breaks the rules at work by stealing photographs, giving discounts, and giving away a disposable camera.

Eventually his misdeeds catch up with him, he loses everything he has left – his job and therefore his customers, and that works as motivation for Sy to involve himself in Will’s affair. With nothing left, he decides it’s time Will pay his fair share too.

Sy’s first real betrayal of hope arrives, while looking in on the Yorkin family eating dinner, expecting Nina to stand up for herself and reveal that she knows about the affair. When she doesn’t, Sy’s frustration is tangible, he expresses, “what is wrong with these people?”

When his horribly invasive and extremely tense fantasy of being in the Yorkin house, using the bathroom and watching football, finally broke, when he was revealed to actually be in his car looking in, conflict rose up within him.

This is clear when he talks about “hunting” his ex-boss’s daughter (with a camera), or when he’s brought to his final act of coercing Will and his lover Maya into faking sexual acts at the end of a hunting knife for his camera. He can’t help himself but to do something, anything, to make things right, to mourn the loss of his fantasy.

Falsehoods & High Tension

There are at least two layers of falsehoods at play here – perfectly intertwined to hold us in their grip.

First, the notion of the film itself, the framework, and the very structure of which we are led to trust, as we have so many times before. We are lured by a false sense of security that comes from sitting in a darkened room, watching along, taking part in the fantasy of the movie ourselves, suspending belief for a couple of hours.

This is a lie we tell ourselves, a lie we forget once we become increasingly involved in the film.

Then, there is a second layer. When Sy is detained by the police, he is asked one question without counsel present – “why?” His experience, narrated by him, makes up most of the movie. The movie is his answer, and his answer is fraught with deception.

His delusions, the lies he tells himself about his role in the Yorkin family, strings us along. He can’t help but see it this way, and thus, neither can we. We go along with it for as long as we can bear it, deceived and tempted to believe.

In this way, the film hangs on to every bit of information until it absolutely needs to be revealed, racking up intense tension, and involving us at every turn. Perhaps we even begin to insert our feelings into Sy’s life.

Turn It On Me

This begs the question – what does that make me, the audience member? Raising my expectations for Sy as a sex offfender, a murderer, and a thief?

The film poses a number of lies and from those lies light is shed on my sick mind and perhaps the sick culture I am a part of.

In that way, I can only conclude that a major piece of this film’s intentions is cultural criticism. A lack of sensitivity for those who are in the most pain among us, for those that may become dangerous because they are ignored.

So, my proposition, in a sense, is to say that One Hour Photo will make you aware of our tendencies as a society to look for the absolute worst in someone’s character. I found myself even hoping for it, getting anxious for it, effectively exposing a piece of our culture for what it really is – ugly.

From a lie, comes a truth.

Without a doubt, what Sy did was wrong – or at very least creepy. And yet, he never went all the way through with it, as might be expected. The fact is he never does use that hunting knife or actually take photographs of the sexual acts he forced between Will and Maya.

The truth is, I saw him cuffed in that interrogation room, lining up photographs of furniture, and I actually felt bad for him – again.

Voyeurism

We’re not terribly different from Sy, partaking in a film as an audience. We feel safe, sitting in a theater or in our living rooms, looking through a bright window into another world, participating, hungry for more action, more drama, more sex. It’s voyeuristic at best, and perverted at worst.

But, it’s okay, we allow ourselves to do it, we don’t go so far as to sit out in front of a stranger’s house or visit a stranger’s kid at soccer practice. Or, do we?

With the breakthrough of social media, in a way we too maintain walls of photographs, looking in on others’ lives and inviting others to look in on ours. So, perhaps we’re not too far off after all and that fact is uncomfortable.

We may take comfort in our own darkened rooms, but just like Sy looking in on the Yorkins, we’re looking in on his life, on his frustration and pain, and we’re feeling something too.

It’s easy to insert yourself into the narrative of One Hour Photo, perhaps even barking out at the flickering screen with anxiety really believing he will be caught trespassing, watching football in the Yorkin’s house. Luckily, at the very last moment, just as the door handle is twisting, Romanek cuts to Sy in his car, revealing it all as fantasy.

At that very moment, when relief breaks and the adrenaline in our blood thins, our trust for the film begins to fracture. What is real and what isn’t?

Sy involved himself in this family’s life, imagined his photo on their refrigerator, and through a twisted sort of love, went through great lengths to try and protect Nina and Jakob from their own lives – from her own cheating husband and father.

This stands as a major break from the security and simplicity of voyeurism, to see but not be seen. Sy tore himself down for the sake of the Yorkin’s and I’m not sure what he got out of it. Certainly not a family or even friends.

Perhaps, only my pity.

Cinematography, Editing, Lighting, and Cleanliness

From the very start of the film, the frames, camera movements, and cuts are striking and fluid, never wasting a moment.

Precision cutting and camera movements from lights out in Jakob’s room to a lamp beside Sy’s hamster’s cage is a good example. It’s a fantastic transition, connecting Jakob’s worries about Sy’s sadness, his mother’s reassurances, and the truth of Sy’s existence.

Sy is often contained using various objects and sets and as often as possible within the frame, causing him to appear to be in a photograph himself – carefully placed and often, for a few moments, unmoving. This is a brilliant stroke of artistry and use of technique. This visual information conveys he is entrapped by loneliness.

Devoid of clutter, the pristine aisles of SavMart, of the warehouse, of the photo lab shelves, of Sy’s apartment, of the Chinese restaurant, of the Yorkin house, of the hotel rooms, of the hunting blade in the sink – it all worked beautifully to empty out Sy’s inner life – no clutter, only emptiness, loneliness and a delusion that he could be “Uncle Sy.”

He participates in this emptying too, when he returns a fallen teddy bear to the shelf at SavMart it’s as though he’s meticulously attempting to keep himself together – pristine and in order – and empty.

Lighting here is fantastic – always hearkening back to the sickly greens and whites of fluorescent bulbs of the photo lab – which he can’t escape no matter where he goes. The deep reds of the darkroom, jarring and alluding perfectly to Sy’s breakdown and inner turmoil.

Television Shows and a Cracked Windshield

The television is used as a device for foreshadowing. Focusing on a clip from the Simpsons alluding murder is all part of Romanek’s set up and eventual deceit – his lie meant to raise the stakes and our expectations – preparing to reflect on our sick minds and our sick culture – by referencing our culture itself on the television, (our ultimate culture machine). It foreshadows a lie, and allows Sy the potential to do horrible things.

I can’t quite crack the meaning of the cracked windshield on Sy’s car. A reference to the pressures of life perhaps, suggesting that Sy’s conscience is beginning to fracture under the pressure of his obsessions and deceit. Whatever it means, it is the beginning of the end.

Robin Williams as Sy The Photo Guy – A Blonde

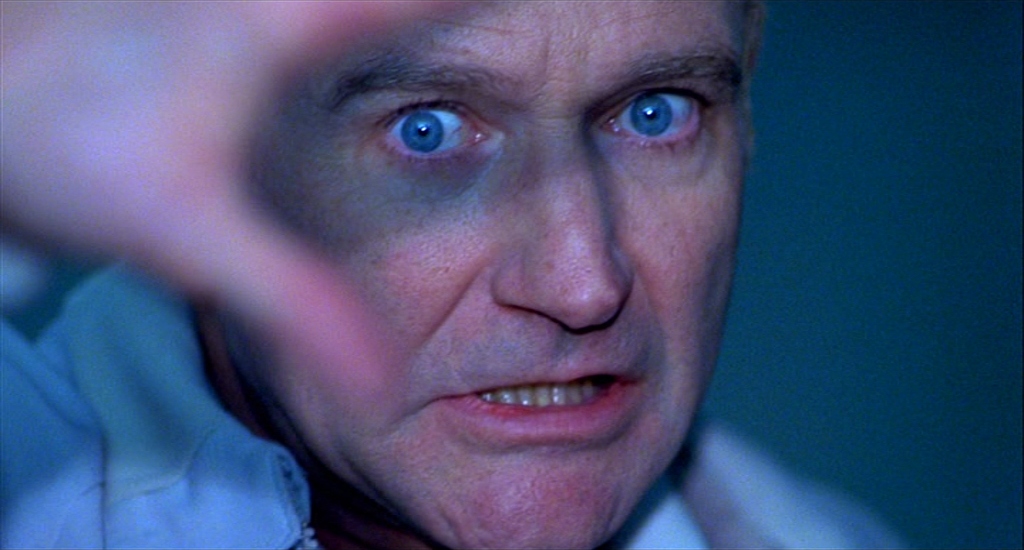

Robin Williams turned in an astounding performance – one of a tortured, lonely, at times pathetic, often manic and creepy, and terribly complicated character with an extremely conflicted inner life.

On the brink, and terribly tense, his actions and love of the Yorkin’s a perversion of his work and life. He’s helpless.

Williams’ work is a balancing act, walking dangerously close to the line but never committing to assault, murder, or invasion. Only ever watching, teasing these things, and most importantly, photographing it.

Self-Pointing Finger

One Hour Photo is an incredibly interesting watch, stretching the capacity of the mind to heights of disbelief, taking in the lies of the filmmaker and the characters to divine the worst.

A final betrayal points a finger back at us, the audience, calling us and our culture out for our sick presumptions and extreme expectations.

One Hour Photo

Writer/Director: Mark Romanek

Stars: Robin Williams, Connie Nelson, Michael Vartan

Movie screenshots courtesy of film-grab.com/Images property of Fox Searchlight Pictures